How Does the One Child Policy Affect the Chinese Family Culturally

The 20th century witnessed the nascency of modernistic family unit planning and its effects on the fertility of hundreds of millions of couples effectually the world. In 1979, Cathay formally initiated i of the earth's strictest family planning programs—the "one child policy." Despite its obvious significance, the policy has been significantly understudied. Data limitations and a lack of detailed documentation have hindered researchers. However, it appears clear that the policy has affected Red china'due south economy and society in ways that extend well across its fertility rate.

Pros

Due to big variation in how the one kid policy was implemented beyond regions and ethnicities, researchers are able to exploit natural variation in their analyses, which makes empirical results reliable.

Strictness of policy implementation is associated with promotion incentives for local leaders.

The i child policy significantly curbed population growth, though there is no consensus on the magnitude.

Nether the policy, households tried to have additional children without breaking the constabulary; some unintended consequences include higher reported rates of twin births and more Han-minority marriages.

Cons

There is no solid show that the one child policy contributed to human uppercase accumulation through the traditional "quantity–quality" trade-off channel.

Current economic studies mainly focus on short-term effects, while the long-term or lagged effects are substantially understudied; thus, statements about consequences and suggestions for policy designs are still missing.

The i kid policy is associated with significant problems, such as an unbalanced sex activity ratio, increased crime, and individual dissatisfaction toward the government.

China's one child policy is maybe the largest social experiment in the history of the human race. The beliefs responses to the policy offering important insights for other studies in labor, development, and public economic science. To date, researchers take found that a series of outcomes, such as a lower fertility charge per unit, an unbalanced sex activity ratio at nascence, and college human capital, are potentially associated with the policy. However, the answers to many important questions are far from satisfactory, and some (e.g. the long-term effects on lifecycle outcomes) have received picayune attending.

The 20th century included the inception of modern family planning, which restricted the fertility of hundreds of millions of couples effectually the world. Due to concerns almost the world's unprecedented rate of population growth in the mid-20th century, some assist agencies and international organizations began to support the establishment of family planning programs. About 40 years after, in the mid-1990s, big-scale family planning programs were active in 115 countries.

China's "one child policy" (OCP) is the largest among the globe's family planning programs. In the 1970s, after ii decades of explicitly encouraging population growth, policymakers in China began enacting a series of measures to curb information technology. The OCP was formally initiated in 1979 and firmly established beyond the country in 1980. It was the first fourth dimension that family planning policy became formal law in China. Differing from nascency control policies in many other countries, the OCP assigned a compulsory general "one-birth" quota to each couple, though its implementation has varied considerably across regions for unlike ethnicities at different times. The policy affected millions of couples and lasted more than xxx years. According to the World Banking concern, the fertility rate in Cathay dropped from 2.81 in 1979 to 1.51 in 2000. The reduced fertility rate is probable to accept affected the Chinese labor market profoundly.

Despite its grand telescopic, due to data limitations, the literature on the OCP is relatively small. This article reviews some of the recent studies on the topic, with a focus on the policy'due south potential social and economical consequences, including consequences related to fertility, sex ratios, and education, as well as private behavior responses, such as changes to reported twin births and interethnic marriages. By comparison the results of the existing literature and ongoing studies in China to those in other countries, it appears that the OCP has had a large and persistent impact on many aspects of club. Investigating these impacts may shed calorie-free on related issues in other realms of research, such as economics, demographics, and sociology.

Variations in OCP implementation

In 1979, the Chinese government formally initiated the OCP to alleviate social, economic, and ecology problems such as the high unemployment rate and scarcity of land resources. In recognition of diverse demographic and socio-economic conditions across China, the central authorities issued "Document eleven" in February 1982 which allowed provincial governments to effect specific and locally adjusted regulations. Two years later, the central government issued "Certificate 7" which farther stipulated that regulations regarding birth command were to exist fabricated in accordance with local conditions and were to be canonical by the provincial Standing Committee of the People'due south Congress and provincial-level governments. This document devolved responsibleness from the key government to the local and provincial governments.

As opposed to many family planning policies in other countries, the OCP was compulsory rather than voluntary. As the name suggests, the policy restricted a couple to having just one child. Notwithstanding, at that place were some exemptions. The nascence quota varied according to residence (urban/rural) and ethnicity (Han/not-Han). Since Han ethnicity is by far the largest in China, bookkeeping for 93% of the population, the policy mainly restricted the fertility of people with Han ethnicity. In general, Han households in urban regions were only allowed to have one child, while most households in rural areas could have a second child if their first was female (this exception is called the "one-and-a-one-half-child policy"). Meanwhile, in most regions, households of non-Han ethnicity were allowed to have ii or 3 children, regardless of gender.

A ofttimes used measure in studies of the OCP is the average monetary penalisation rate for 1 unauthorized birth in the province-year from 1979 to 2000. The OCP regulatory fine (which is called the "social child-raising fee" in People's republic of china, and for brevity is referred to as the "policy fine" in this article) is formulated in multiples of annual income. Though the monetary penalty is only one attribute of the policy, and the authorities may take other authoritative actions (e.yard. loss of party membership or employment), information technology is still a good proxy for the policy considering an increment in fines is usually associated with other stricter policies. The Illustration shows the design of policy fines from 1980 to 2000 in selected provinces and nationwide.

At the very beginning of the OCP, Vice Premier Muhua Chen proposed that it would be necessary to pass new legislation imposing penalties on unauthorized births. Nevertheless, subnational leaders faced practical difficulties in collecting penalties in addition to resistance and complaints from the populace. For case, Guangdong province received more than 5,000 letters lament about the implementation of the OCP in 1984. In response, the primal government fully authorized the provincial governments to determine their own "tax rates" for excessive births with the issuance of Document 7 in 1984. Considering local governments were more concerned about social stability than the central authorities, they had niggling incentive to design a high penalty rate. Consistent with the Illustration, some local governments even lowered penalization rates after 1984, and, until 1989, there were few changes in fertility penalties.

A major change in fine rates occurred at the cease of the 1980s though, when the central authorities linked the success of fertility command to promotions for local officials. As stated in the book Governing China'south Population: "Addressing governors in spring 1989 Li Peng (electric current premier) said that population remained in a race with grain, the outcome of which would affect the survival of the Chinese race. To achieve subnational compliance, policy must be supplemented with more detailed management by objectives (ME 890406). At a meeting on nativity policy in the premier'due south part, Li Peng explained that such targets should be 'evaluative'" [ii].

In March 1991, to show resoluteness, the central government listed family planning among the three bones state policies in Communist china'south Eighth V-Year Programme passed past the National People's Council. The Eighth Five-Year Plan explicitly set a goal of reducing the natural growth rate of the state's population to less than 1.25% on boilerplate during the following decade. To attain such a challenging objective, national leaders employed a "responsibility system" to induce subnational or provincial officials to set high fine rates.

During the brusk period betwixt 1989 and 1992, over half of the state's provinces (xvi out of 30) saw a pregnant increase in their fine charge per unit, with the average rate increasing from i.0 to ii.8 times a household'south yearly income. Indeed, 16 of the 21 significant increases in the policy's history (i.e. increases of more than 1 times a household's income) occurred during this menstruation.

There is a potent correlation between increases in fine rates and the incidence of government successions. Among the 16 significant increases, 12 happened during the first two years of new provincial governors' tenures. Governors who instituted fine increases had college chances of being promoted than their peers, and several rose to pregnant heights within the fundamental government. In addition, provincial governors who increased fertility fines tended to be younger. The average age of these sixteen provincial governors was 56, which was significantly lower than the boilerplate age of other provincial governors (59 years). These numbers suggest that the promotion incentive for provincial governors could be a major driving force for the changes in fertility fines. This is also consequent with the premise that the incentive to raise fine rates depends on a governor'southward personal characteristics, such equally inauguration time and age.

The corporeality collected via the policy fine was non made public until recently: the total was about 20 billion RMB yuan (US$ three.3 billion) among 24 provinces that reported fine rates in 2012. For example, Guangdong, one of the richest provinces in China, nerveless 1.v billion yuan in 2012. Meanwhile, equally a comparison, full local authorities expenditure on compulsory schooling in the province was ten.five billion.

Empirical approaches to identify the effects of the OCP

A recent review of the literature summarizes four empirical approaches to place the effects of the OCP [3].

The start approach uses the initial year of the policy, 1979, as a cutoff and compares the birth behaviors of women before and later on implementation of the OCP. Under this approach, observations before 1979 class the control group and those later on 1979 the treatment group. In general, this approach assumes in that location would be no change in the outcome variable (eastward.g. birth rate) after 1979 if in that location was no fertility restriction.

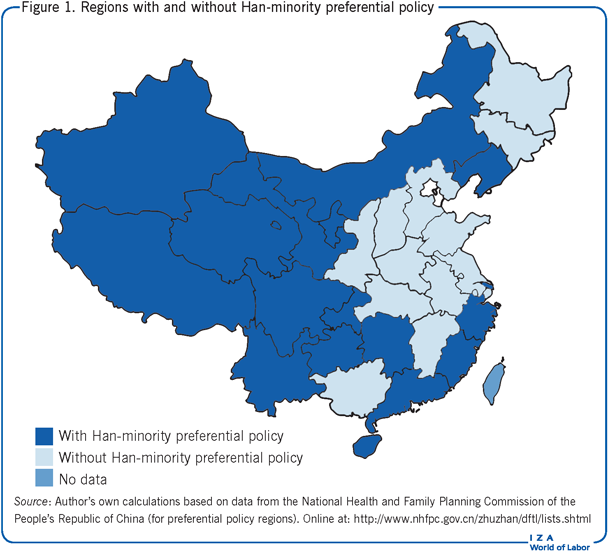

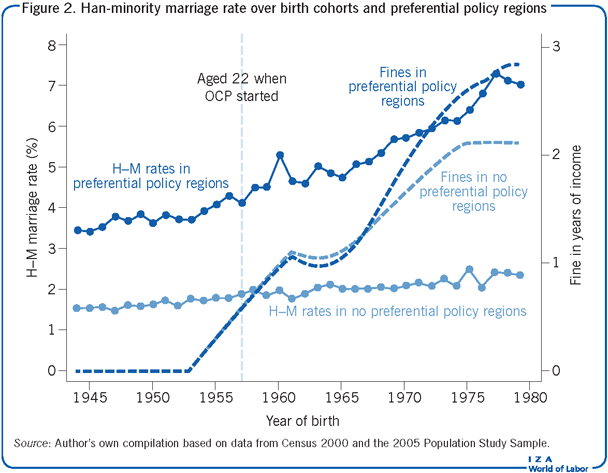

The second arroyo compares the outcomes of Han Chinese and minorities before and after policy implementation in a difference-in-differences framework. Nether this approach, minorities are used every bit the control group and Han people as the treatment group. This methodology requires that the changes in effect variables of Han and minorities be the aforementioned without the OCP and assumes that minorities' outcomes are non affected by the OCP. However, this requires a instance-by-case assay and one needs to exist careful when drawing causal interpretations. For example, considering Han-minority couples are allowed to give birth to a 2nd child in sure regions (as shown in Figure 1), Han people have stronger incentives to marry minorities to obtain the actress nascency quota. One straight effect is a higher Han-minority marriage rate in regions with this preferential policy, equally shown in Figure 2.

The tertiary approach exploits the cantankerous-sectional and temporal variations on fines for an illegal birth. As noted before, the fines change over fourth dimension; it is thus plausible to exploit these variations to identify the effects of the fines. Unfortunately, in that location is no formal or authentic documentation for why the fines change. Furthermore, these changes may only reverberate 1 attribute of the policy'southward effects. Therefore, farther justification is required to validate the utilize of fines equally the main independent variable.

The fourth approach explores variation betwixt the intensity of OCP implementation beyond different regions in combination with the differential length of exposure of different birth cohorts to the OCP. Specifically, this approach constructs a measure based on backlog births to Han women over and above the i child rule in each region while decision-making for pre-existing fertility and community socio-economic condition. However, as noted in one recent study, this arroyo relies on the strong assumption that any unobserved region-specific shocks to fertility or other family unit outcomes over time are uncorrelated with the cross-sectional measure of the OCP enforcement intensity [three].

It should be noted that these four approaches are not exclusive. Some ongoing projects are employing several of them at once. Given that official documentation on the policy is limited, researchers are likely to develop more than empirical approaches in the future to address the electric current issues, such as data limitations, and gain a more complete understanding of the OCP.

Furnishings of the OCP on fertility and the sexual practice ratio

Since the main goal of the OCP was to restrict population growth, the first question to ask is whether it has been successful in this respect. The answer is generally yes, though the magnitude of its success varies co-ordinate to different studies.

Some early studies investigated how fertility responded to the policy's restrictions [4]. Their findings are consistent, in full general. For example, information technology was plant that a one standard difference increase in the prevalence of contraceptives led to a 0.5 standard deviation decrease in the total fertility rate.

However, the findings in the more recent literature are mixed. For instance, one study used improved measures of policy to propose that if earlier family unit planning policies had not been replaced by the OCP, fertility would still have declined below the replacement level, and that the additional effects of the OCP were fairly limited [5]. By dissimilarity, a study from 2011 used two rounds of the Chinese Population Census and found that the OCP has had a large negative effect on fertility; the average effect on mail service-handling cohorts' probability of having a second kid is every bit large as -11 per centum points [6]. Therefore, while scholars tend to agree that the OCP has had significant effects on fertility, determining the magnitude of these effects remains an important and unanswered question.

Another demographic outcome unremarkably investigated in the literature is sex ratio. Incidentally correlated with the introduction of the OCP, the sex ratio at birth (i.due east. males to females) increased by 0.2 over the course of 25 years, from 0.95 in 1980 to 1.15 in 2005. This phenomenon has been termed "missing women" by Amartya Sen. Since there is a strong preference for male children in People's republic of china, restrictions accept led to parents selecting to accept/not take a child based on the results of ultrasonography technology [7]. Because parents take been able to cull abortion instead of having a girl, many researchers argue that the OCP has contributed to the high sexual practice ratio in Communist china. Ane study exploited the regional and temporal variation in fines levied for unauthorized births and found that college fine regimes are associated with higher ratios of males to females [1]. The results are particularly true for the second or third births: a 100% increase in the fine charge per unit is associated with a 0.8 and 2.three percentage point increment in the probability of having a male child in the second and 3rd births, respectively. One of the previously mentioned studies used a dissimilar methodology, but reached a similar finding [vi]. The study suggests that the effect of the OCP accounts for near 57% and 54% of the total increase in sex ratios for the 1991–2000 and 2001–2005 birth cohorts, respectively.

The imbalanced sex ratio may assistance to explain some puzzling phenomena in People's republic of china, such as a high saving charge per unit. In turn, this can be viewed as a possible upshot of the OCP. For example, 1 study found that as the sexual activity ratio rises, Chinese parents with a son increase their savings rate in order to improve their son's relative bewitchery for wedlock [8]. They detect that the increment in the sex ratio from 1990 to 2007 can explain about sixty% of the bodily increase in the household savings rate during the same menses.

Furthermore, the imbalanced sex ratio may pb to other serious social consequences, including increased crime. Ane study used the exogenous variation in sex ratio caused past the OCP to encounter its effect on crime and found an elasticity of law-breaking with respect to the sexual activity ratio of 16- to 25-twelvemonth-olds of iii.4, suggesting that male sex ratios tin account for i-7th of the rise in crime [7]. The written report proposes that i possible mechanism for this increase could exist the agin wedlock market due to the unbalanced sex ratio.

Effects of the OCP on human capital accumulation

One established relationship between fertility and human majuscule accumulation is the child quantity–quality trade-off. Nonetheless, many empirical economists take examined the relationship in the case of Red china and establish mixed evidence. The OCP used birth quotas to control population growth. As such, it provides a potential external daze to the size of families and thus enables one to written report causality betwixt family size and children's didactics.

One analysis used the plausibly exogenous changes in family size caused past relaxations in the OCP to estimate the effect of the number of children in a family unit on school enrollment for the outset child [9]. Surprisingly, the results show that having an boosted kid increased the likelihood of schoolhouse enrollment of the first child past almost 16 pct points, implying the relationship between quantity and quality is not a "trade-off," merely rather "complementary." The author provides several explanations, including greater economies of scale, enhanced permanent income, and increased labor supply of mothers.

Taking an alternating approach, another study exploited the exogenous variation in twin births in dissimilar nascency orders to estimate the potential gain in homo capital by policy-induced compressed family unit size [10]. The authors used the policy's characteristics to tell the story: producing twins on the starting time birth results in an exogenous shock to family size in urban regions, whereas having twins on the second birth represents an exogenous shock to family size in rural regions considering parents in these areas are already allowed to have a 2nd child. The results evidence a modest merely positive result of compressed family unit size induced by the OCP on man capital letter, as measured by health and teaching.

The above findings suggest that the effects of the OCP on human being uppercase are not well established when just considering the quality–quantity merchandise-off. For example, a study from 2010 investigated the impact of fertility policies on the socio-economical status and labor supply of women aged fifteen–49 years in Colombia. The results suggest that women impacted by birth control policy during their teenage years are more probable to have college instruction. I possible caption is that people are more than incentivized to achieve higher education if they expect to accept lower fertility. As opposed to the quality–quantity trade-off, which just affects post-policy birth cohorts, the effects from lower fertility expectations may be present among those who were born before the policy'southward implementation, merely grew up during its tenure. This finding calls for further test of the OCP's bear upon on human being uppercase accumulation. This is important because information technology suggests another explanation for how fertility affects economic growth.

Discussion on the OCP's effects on human being capital is still ongoing. The varied findings imply that the answer to the human majuscule question may depend on the individuals/cohorts examined and on the model specification employed. Although information technology is difficult to respond whether and to what extent the OCP increased homo uppercase, the policy itself provides plausibly exogenous variations for future studies to examine.

Effects of the OCP on other family outcomes

Other outcomes, such as divorce, labor supply, and rural-to-urban migration have received less attention in the literature, though they are investigated in a recent study [3]. The results propose that regions with stricter fertility policy enforcement tend to have a greater likelihood of divorce, college male labor force participation rates, and more rural-to-urban migration; however, these effects are modest. A 1 standard difference increase in policy enforcement (measured past excess fertility, as mentioned in the fourth approach presented previously) leads to a 0.015 percentage indicate college divorce rate, a 0.12 percent point higher male labor force participation rate, and a 0.8 per centum indicate higher rural-to-urban migration charge per unit. The results suggest that lower birth rates may have some unintended consequences that scholars and policymakers need to consider.

Another interesting miracle is the increased rate of twin births. When a couple is allowed one kid, the simply legitimate way to take 2 children is to give birth to twins, which is largely out of the command of the couple. For those who do non give birth to twins, an alternative is to report fake twins, that is, to register two consecutive siblings as twins. Interestingly, the rate of twin births reported in population censuses more than doubled betwixt the late 1960s and the early 2000s, from three.5 to seven.v per 1,000 births. A contempo study suggests that at least one-3rd of the increase in twins since the 1970s can exist explained by the OCP [11]. Since couples can intentionally have twin births to bypass the OCP (i.east. by reporting fake twins or taking fertility drugs to accept multiple births), the distribution of reported twins in China may not be random.

One limitation of studying the impact of the OCP may exist the measures employed. Because this policy was implemented essentially at once beyond the unabridged country, lilliputian variation exists in the timing. Because of this, many scholars have relied on the differential treatment of Han and minority ethnicities to evaluate the policy's furnishings. However, this is not a perfect approach because different characteristics across the ethnicities may be correlated with the time trends, thereby biasing the results.

In addition, local governments usually had a "policy bundle" when implementing the OCP, which often included different penalties for illegal births for people from different backgrounds. For example, when an illegal birth is observed, those with party membership may lose information technology, and those hired past the public sector or collective firms may lose their jobs. These measures may go hand in hand with policy fines, simply they are hard to quantify.

Furthermore, since the literature relates beliefs response to social welfare, economists usually examine individuals' behavioral responses to authorities policies to estimate the corresponding social welfare loss. Yet, no written report has so far examined the corresponding welfare loss for fertility policies. To practise this, researchers may need to build upwards a model and so analyze rich data sets to provide relevant empirical evidence. However, the difficulty in this regard originates from the lack of official documentation or details regarding the implementation of People's republic of china'due south OCP.

Finally, the electric current literature on the OCP mainly investigates the simultaneous or curt-term effects. Specifically, information technology compares how individual behaviors differ before and later the implementation of the policy. However, in that location is piffling evidence on the long-term or lagged effects of the OCP. Take the report from 2010 every bit an example, whose results suggest that women growing up nether birth restrictions may have higher socio-economical status [12]. Because this, the lower fertility expectations resulting from the OCP may atomic number 82 to higher didactics, and this potentially has profound and long-lasting effects on productivity and economical growth. Nonetheless, this is largely unknown in the electric current literature.

As the largest social experiment in human being history, the OCP has restricted the fertility of millions of couples in Prc for more than three decades. This article has reviewed outcomes presented in the literature about the OCP, with a focus on its intended and unintended consequences, including fertility, sexual activity ratio, human majuscule, twin births, and interethnic marriages. The results suggest that the policy has had large and long-lasting impacts on many aspects of both the economy and society, though debates persist on certain topics. The current findings also provide possible directions for insightful future studies.

Information technology is hard to conclude whether the OCP has been adept or bad in general. It has curbed the potentially problematic population blast in China, though researchers disagree as to how much of that should exist attributed to the OCP, and it has peradventure increased human being capital accumulation. Only, information technology has too brought with it problems, such as an unbalanced sex ratio, increased criminal offense, and individual dissatisfaction toward the government. Since 2010, the regime has loosened the policy restrictions. In tardily 2013, People's republic of china's government started the "selective two child policy." This policy allows couples to have 2 children if one fellow member of the couple has no siblings. In November 2015, the regime ended the OCP and started the "universal two kid policy." Although the OCP has at present been terminated, there are many important questions that accept yet to be answered. Until considerable further inquiry is done, information technology is difficult to extrapolate lessons from People's republic of china's experience to inform future policy decisions.

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA Earth of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on before drafts. Previous work of the author contains a larger number of background references for the fabric presented hither and has been used intensively in all major parts of this commodity [11].

Source: https://wol.iza.org/articles/how-does-the-one-child-policy-impact-social-and-economic-outcomes/long

Posting Komentar untuk "How Does the One Child Policy Affect the Chinese Family Culturally"